of Janne Haaland Matlary

In Norway the Parliament adopted a law on “gender-neutral” marriage on June 11th, 2008. There is a large majority behind this law, both in terms of public opinion and in parliament itself. There is a clear perception that everyone has a right to marry and a right to have children. The law includes the right to adopt children born to homosexual couples through the tecniques of insemination. Egg donation and surrogate motherhood are still prohibited in Norway, but semen donation is legal. When the law is passed, children “procured” by same-sex couples can be adopted by the non-biological “parent” in the relationship.

It seems clear that no notion about human nature, including its biological aspects, is regarded as a constant and given.

In this situation where the Zeitgeist is that all can be deconstructed and reconstructed, it is time to consider the deeper problems of current Western, especially European, politics. The degree of relativism is now so great that there are no common Grundwerte on the anthropological side. It seems impossible to discuss what a human being is in European politics today.

Why is this so? What does it mean for European democracy? Can it be remedied, if so, how?

I have recently published a book about this problem in several languages, including Italian. (Diritti umani abbandonati? La minaccia di una dittatura del relativismo, Eupress FTL, Lugano, 2007). My intervention here is based on this book.

In her analysis Rights Talk from 1991, Harvard law professor Mary Ann Glendon writes that “discourse about rights has become the principal language that we use in public settings to discuss weighty questions of right and wrong, but time and again it proves inadequate, or leads to a standoff of one right against another. The problem is not , however, as some contend, with the very notion of rights, or with our strong rights tradition. It is with a new version of rights discourse that has achieved dominance over the last thirty years” (Glendon, 1991:x). This new rights discourse is characterized, says Glendon, by the proclamation of ever new rights that are the properties of ‘the lone-rights bearer’ as she aptly calls him, one who has no duties and who pursues his own interests in the form of ‘new rights: “As various new rights are proclaimed and proposed, the catalog of individual liberties expands without much consideration of the ends to which they are oriented, their relationship to one another, to corresponding responsibilities, or to the general welfare” (Ibid. XI).

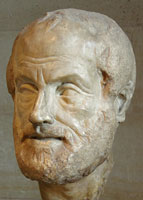

| Hans Frank at the Nuremberg trial. Frank confessed to some of the charges put against him and viewed his own execution as a form of atonement for his sins. In the days of captivity, he returned to the Roman-Catholic Faith of his childhood. |  |

Human rights were codified as a response to the political and legal relativism of Hitler’s Germany and World War II; which put in a nutshell the relativist problem of obeying orders from the legal ruler of the realm – in this case Hitler – when these orders were contrary to morality. The Nuremburg trials laid down that it is wrong to obey such orders; that there is in fact a ‘higher law’ – a natural law if you will – that not only forbids compliance, but which also makes it a crime to follow such orders. In the wake of this revolutionary conclusion in international affairs – it was the first time in history where a court had adjudicated in such a way - there was a growing movement to specify what this ‘natural law’ for the human being entailed. This resulted in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights only three years late, a supra-national set of inherent and inalienable rights for every human being. It is very clear that the statement of human rights was to be a ‘common standard for all mankind’, as states in the preamble, and not something that could be changed at will by political actors. Yet this is exactly what happens in Europe today.

The rights defined in this document are parts of a whole, making up a fullness of rights which reflect a very specific anthropology. The rights are clear and concise, and the underlying anthropology is equally clear. The intention of the authors of the declaration was to put into a solemn document the insight about human dignity that could be gleaned from an honest examination, through reason and experience, of what the human being is. Therefore they wrote explicitly that ‘these rights are inviolable and inherent’. In other words, these rights could not be changed by politicians or others, because they were inborn, belonging to every human being as a birth-right, by virtue of being a human being. The declaration is a natural law document which was put into paragraphs by representatives from all the world, from all regions and religions. Human rights are pre-political in the sense that they are not given or granted by any politicians to their citizens, but are ‘discovered’ through human reasoning as being constitutive of the human being itself. They are also therefore apolitical because they are not political constructs, but anthropological – consequences of our human nature. As one of the key drafters of the declaration, Charles Malik, said; “When we disagree about what human rights mean, we disagree about what human nature is” (Glendon, 2001:39). The very concept of human rights is therefore only meaningful if we agree that there is one common human nature which can be known through the discovery of reason.

This last statement is however at great odds with contemporary mentality, which is relativist and subjectivist, scorning the idea that human nature as such exists and even more so that it can be known through reason. But if this is denied, and we regard human rights as something that mere political processes can change, how can we uphold human rights as a standard for others, if not for ourselves?

|

Pro Choice propaganda: Abortion as a private matter |

But in Europe today there is no clear basis of human rights, but an intense struggle over the interpretation of these rights, and often a major discrepancy between what a state proclaims in solemn international conferences and domestic policy. The EU constitutional treaty has left out the key terms ‘inherent’ and ‘inalienable’ in the bill of rights, and has failed to retain the language on heterosexual marriage and family.

In more general terms, while ‘the right to life’ is the first and primary human right according to the Universal Declaration; most European states have had abortion on the law books for many decades. While the right to marry is defined as a right for ‘every man and woman’ in the same declaration, same-sex ‘marriage’ is increasingly introduced in European states. While children have a right to know and be raised by their biological parents or in a similar situation according to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), this seems to be ignored when children are ‘produced’ from anonymous donors. While the family is firmly defined as the basic and natural cell of society in the declaration, it is redefined by many nation states and often the state does not have policies that support the family. While the right to special societal protection for mother and child is defined in the declaration, motherhood is often regarded as a drawback for women in the European labour market, and mothers are discriminated against. While the family has a right to a sustainable income: just wage, in the declaration, labour rights are more and more neglected in European states and individual taxation makes a mockery of the ‘family income’ concept. While religious freedom includes the right to public and private worship, Muslims are met with suspicion and opposition when they want to erect a mosque, and other religions, including the predominant one in Europe, Christianity; is sought pushed back into the private sphere.

As stated, there is a curious situation; a paradox, in the many discrepancies between the human rights professed, especially abroad, and the political reality at home in Europe.

But the paradox is even more glaring when we consider the trend towards not defining the values underlying European democracy. By this I mean the trend towards complete subjectivism, even nihilism: you have your opinion; I have mine; and those that say that there are objective definitions of norms – Grundbegriffe - are fundamentalist and undemocratic. This trend is extremely dangerous; as this kind of subjectivism undermines democracy and paves the way for totalitarianism: might then eventually becomes right when there is no standard by which to determine right. The old ideological differences are mostly gone after the Cold War, and have not been replaced. Instead, individual preferences predominate politics.

The trend towards nihilism, a hundred years after Friedrich Nietzsche wrote ‘Beyond good an evil’(1), aptly sub-titled “Precursor to a philosophy for the future”, is manifested in the lack of belief in human ability, through reasoned debate and thinking, to arrive at objective truth about human nature and human virtue and vice. This stance is pronounced and implicit in European politics today. The very concept of truth itself is not only contested; as it has always been, but seen as fundamentalist and repressive; as something undemocratic.

This strange aversion to the concept of truth is intimately linked to the concept of ‘political correctness’ (PC). It is perhaps the most powerful concept we have in our modern Western democracies, and is a wholly immaterial one. The power of being PC or not has been felt by most people: one senses that something which used to be ‘comme it faut’, suddenly is not. The media no doubt play a key role in this process of ‘shaming’ and ‘praising’. To think that one can discover objectively valid moral truths is certainly the most ‘un-PC’ position possible. It is however the position argued for in this book.

This subjective, media-driven power of the PC is only possible because there is no search for truth, as that is assumed away as impossible and probably as basically undesirable. But with such a premise, human rights can never exist, for they cannot be defined. The paradox of modern European democracy is exactly this: we profess and impose human rights all over the globe, but refuse to define the substance of these rights at home. We hold that they mean what we choose them to mean at any one time; thereby making PC the guiding star of politics. The majority of voters do not speak out in referenda on these issues, but so-called ‘public opinion’ is moulded in media-driven campaigns, often in clever alliances with single-interest groups. Part of this ‘norm entrepreneurship’ is to ‘shame’ and intimidate minority views and to create an appearance of majority opinion through clever uses of the media. Thus, in this way the ‘tolerance’ claimed becomes deeply intolerant.

The end result is that might becomes right, the logical implication of extreme subjectivism. Can the Grundwerte be defined? Can there be an objective discussion about ethics? I now turn to the analysis of professor Ratzinger in this regard:

A Rationality that embraces Ethics?

The current paradigm of rationality is based on the idea that rationality (Vernuft) is independent of both creator and human being. This is, underlines Raztinger, entirely true when we speak about natural science: “Sie beruhen auf einer Selbsbegrenzung der Vernuft, die im technischen Bereich erfolgreich und angemessen ist, aber in der Verallgemeinerung der Menschen amputiert” ( ibid., p. 52). The consequence of only accepting this limited form of rationality is that the human being no longer has any idea of how to reason about right and wrong, and that he has no standard of ethics outside of himself: “Sie haben zur Folge, dass der Mensch keine moralische Instanz ausserhalb seiner Berechnungen mehr kennt” (ibid.). This implies that all that is not within the confines of empirical science – all that which relates to political and personal norms and values – are seen as wholly subjectivistic.

Why is this a problem? The difference between a pluralist society and a relativist one lies in the existence of some common norms, Grundrechte in German. Citizens are expected to agree on some things, usually thought about as a ‘social contract’ by political philosophers. For instance, stealing is wrong and must be punished; stable families are good for the upbringing of future citizens and hence, good for society; etc. But modern relativism denies any common norms beyond those of political correctness. Indeeed, this paradigm leads to a limitless concept of freedom since there are no standards or limits outside subjective judgement: “der Freiheitsbegriff scheint grenzenlos zu wachsen “ (ibid., p. 52).

Modern European man has cut off his historical roots and regards history and its philosophical insights as invalid for him. The real progress in natural science has led to the misunderstanding that a similar progress has taken place in human ‘science’. Not only is modern man totally ignorant of his own philosophical and theological history, but he believes – tragically – that technical and economic progress implies civilisational progress. Also, the state of technical knowledge dictates what one in fact does with and for the human being, because “was man kann, das darf man auch – ein vom Konnens abgetrenntes Durfen gibt es nicht mehr” (ibid., p. 53). “Durfen” – the should – the normative question of ethics – is now regarded as something to be resolved by the power of public opinion and personal preference.

Is functional rationality enough for the human being and for politics? The answer is no. Is this rationality self-sufficient? No, when it is used to decide in non-technical matters, i.e. normative ones.

How can rationality be defined beyond the sphere of technical scientific argument? Can there be a rational determination of basic norms and values? This latter question would seem to be a folly today, even if human rights as a concept are based on the postulate of a human nature that is the cause of human rights: we have human rights because we have human dignity, as each and every preamble to human rights conventions reads. Further, the Nurnberg trials were premised on the existence of a higher moral law that in fact was argued to be common to all human beings and knowable for all human beings. If we accept this on purely pragmatic grounds – i.e. the human rights edifice is based on this postulate – we immediately must ask about this form of rationality – does it exist, how does it work?

Politics is the sphere of the rational

It is very interesting, but not surprising, that professor Ratzinger as Pope Benedict XVI has chosen to write large parts of his first encyclical about rationality. In the second part of Deus caritas est(2) he discusses how rational decisions in political life can be restored. Reason needs constants correction, he states, because “it can never be free of the danger of a certain ethical blindness caused by the dazzling effect of power and special interests” (p. 28). Reason is inborn in man, but can be and is often corrupted. This is the ancient Aristotelian position where virtue and vice are in constant contestation. The Church stands firmly in this tradition of natural law, which is not specifically Christian at all. The only role for the Church in political life, says the Pope, is therefore to argue “on the basis of reason and natural law” , “to help purify reason and to contribute to the acknowledgement and attainment of what is just” (ibid.)

It is because the Church is ‘an expert in humanity’ that she has something to contribute in this respect; and the Church “has to play her part through rational argument” (ibid). The aim is to reawaken a sense of justice in people, which is the essence of rational argument about politics. Justice is one of the four cardinal virtues and the one proper to politics in the writings of classical political philosophy. The Pope distinguishes very sharply between the role of religion and that of politics, stating that “the formation of just structures is not the direct duty of the Church, but belongs to the sphere of politics, the sphere of the autonomous use of reason” (p.29, my emphasis).

The Church should concern herself with souls, and with promoting the truth about human nature – its virtues and vices, its ability for improvement; in short, its spiritual life. But politics is something else, an autonomous sphere which is neither religious nor private, but which has its own ‘mandate’ and rationality. The Pope defines politics as the ‘sphere of the autonomous use of reason’ – not as that of interests or power, but as the sphere of reason.

How can this be? What does this mean?

In his speech to the Benedictine monastery in Subiaco, on receipt of the Premio San Benedetto in April 2005 – some days before he was elected Pope; he underlined that Christianity is the ‘religion of the Logos’ (op.cit., p. x). Logos is the Greek word for reason, in Latin ratio. To be rational is, surprisingly enough, equivalent to being human: the definition in the classical Aristotelian and Platonic philosophic tradition is that the human being is a ‘rational and social animal’. As discussed in previous chapters, rationality is the ability to offer arguments and justifications for something; unlike animals, which also have language and can communicate with each other; the human being is the only entity that can reason about things. Thus, animals fight, make love, procreate, hunt, eat, play and live a communal existence by instinct, but only humans can reason about all these natural activities.

|

The Benedictine monastery in Subiaco |

Morever, ratio defines the human being itself; without reasoning he simply would not be a human being. The ability to reason is inborn in very human being, but it can be destroyed – such as in illess or handicap, and it can be corrupted, such as in people who refuse to discern right from wrong. Having the ability to reason is not equivalent to using that ability.

Ratio enables man to reason about fact as well as value: one can discern truth and falsehood in a factual statement, such as “the house is red”. Unless on is colour-blind, one is able to tell whether this is a true statement or not if one knows the word for ‘red’ and ‘house’. But the same logical ability is present in ethical or moral judgments: an uncorrupted human being can arrive at the conclusion that is it wrong to steal or to kill. The criticism by David Hume much later simply misses the point, because the Aristotelian definition of the human being and his rationality entails ethical ability: Reasoning about ethics is as natural and inborn, and as rational, as is reasoning about empirically observable facts. Animals will most probably steal each others’ prey if they have the chance, whereas humans may do the same and indeed often do, but they nonetheless know that this is wrong. At least they do not believe that it is right.

The modern European rationality is therefore only a partial rationality, as it extends only to technical, mathematical, or empirical knowledge. The entire classical tradition of humanism has been forgotten and suppressed over centuries of skepticism and criticism ala Hume’s. One may object that this tradition has thereby been rendered obsolete by most modern standards, and that it cannot be revived and made usable to the modern, secular human being.

Reviving Natural Law

To this must first be said that the natural law tradition is by no means religiously founded. It is an entirely secular tradition that postulates one premise, viz. that there is a knowable and constant human nature, and that knowledge is arrived at through rational discernment. The Pope, when he was still cardinal, made the point to me in conversations that natural law has to be re-made in modern language; its premises are valid, but one cannot revive a tradition that has been side-lined for so many centuries as it was. While natural science and the natural based on that has progressed; natural law has not really this into account. Moreover, the critical issue is that of the ‘human sciences’, which seem to have regressed rather than progress.(3)

However, in the field of values or norms, natural law thinking has persisted, especially in Catholic philosophy and in the Church itself. In previous chapters in this book I have spent much space showing the absurdity of a totally relativist position, and it is easy to refute such a position. As we have seen, both human rights and democracy are upheld by relativists as ethically right and good, thus making for the paradox that the West proclaims relativism in all things ethical but not in the area of political governance. The contradiction in terms that is evident in the area of human rights is clear: human rights cannot exist as a concept, even less as a reality, if they are based on a relativist position.

The defining characteristic of the human being is ratio, and as the Pope points out, Christianity is the religion of the Logos, of ratio. All things concerning ethics can therefore be discerned by what is often referred to as ‘right reason’, that is, uncorrupted reason. Natural law, which is the term St. Thomas Aquinas uses for the ethics of man’s life in the city, of political life, is entirely accessible to the human mind. Faith as such is even accessible by reason, as evidenced in his logical proofs of the existence of God. Today such proofs are less popular and esteemed, but I mention them simply to underline how far human reason is credited in the Catholic tradition.

|

|

Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas - two fundamental philosphers of the Western civilisation that are loosing influence in modern politics. |

St. Thomas took his knowledge and inspiration directly from Aristotle, via the long ‘detour’of Arab philosophy. If we look at the Aristotelian notion of man, we find the word ousia which means ‘substrate’, something which is in and of itself; underlying all things that change. In Latin, this term is rendered substantia, substance. Essentia, essence, is another expression of this. Genus and other characteristics are ‘accidents’, accidental, but human being is essence, primary and universal.

The definition of the human being as being is therefore that it is an entity that is not derived from anything else; it is the most primary substance, along with other natural creatures such as animals. Aristotle is an empiricist in the sense that he proceeds by observation and classification based on this: he therefore observes that both men and animals are social beings, but that only man is a rational being even if animals also have language, as stated above.

This classical postulate, the definition of the human being by his ration faculty, was adopted by philosophers and theologicans in the early Middle Ages and later, as said, rediscovered by St. Thomas. For instance, Boethius in the 6th century states that man is a ‘rationalis naturae individua substantia’, ‘an individual substance of a rational nature’(4) and the Stoics of the later Stoa in Rome all postulated the rational ability of man in ethical matters as the important characteristic. The ability to discern and to do the right things was termed ‘virtue’, the Latin for manly, strong, derived as it is from the word for man, vir. The cardinal virtues were known and practiced throughout antiquity, from Socrates’ quest for justice in the Platonic dialogues to Marcus Aurelius’ commentaries on how to practice fortitude and temperance in the governing of the Roma empire.

The human being, then, is created with rationality, and indeed this quality is what distinguishes him from animals. The virtues are the characteristics of human nature that allow man to develop; and the corresponding vices are the ways to become less human, to de-humanize oneself. In Aristotelian ontology all beings have a purpose, a telos, and the purpose of the human being is to perfect the virtues and combat the vices. This is so crucial that it is intrinsic to him in the sense that being itself is ‘more or less’ according to how virtuous a person is. A vile person has less reality or being than a virtuous man, and we recognize a remnant of this in the expression ‘de-humanization’ which we use for someone who is really vile. To the relativist this language cannot logically make sense, as virtue and vice are but subjective preferences. Yet people still realize what de-humanization means; someone who is ‘less than’ human.

The telos of man is eudemonia, happiness, but this is not in the sense of pleasures and indulgences, but in the sense of self-disipline, justice, prudence, and temperance. Only the person who fully masters himself is happy, according to the ancient precept. It is told that emperor Marcus Aurelius lived an ascetic and frugal life, a Spartan existence, in order to conquer his passions – among which sexual passion is probably the least important. The ingredients in ethical living were known very precisely: the virtues were all interconnected; parameters whereby one would navigate in everyday life; and vices could only combatted through strength, i.e. virtue. In the Stoic universe detachment from life’s vicissitudes and temptations played a key role, as did the practice of being ready for death. “Death frees the soul from its envelope”, Marcus Aurelius said. Not fearing death gave strength, perspective on life, and the ability to appreciate the here and now in real terms.

When we look at Christian teaching, we redisover the same elements, this time with an addition of supernatural virtue – the theological ones of faith, hope, and charity. In Christianity the ancient programme of character formation continues: one must acquire natural virtues before one can aspire to attain the super-natural ones. In the famous dictum of St. Thomas, “faith builds on nature and perfects it”. There is no point in trying to be a good Christian unless one is prepared to be a good human being; it is simply an impossibility, for divine virtue cannot be attained by a vile person. Forgiveness can of course be dispensed at the discretion of the Lord, but virtue is like an edifice built stone one stone.

What happened to the classical scheme of character formation? Why did people stop believing in the objective truth of virtue and vice, and in human nature itself? This is of course the long story of refutations of metaphysics since the late Renaissance, but it is in many ways a story that is correct and progressive regarding natural science, but which is not so regarding ethics. As professor Rattinger points out, the old precepts of natural law with regard to natural science have been refuted and justly discarded; but this development is not correct with regard to ethics. There has been no Copernican revolution with regard to progress in defining human nature; only a long row of skeptical philosophers who have dispensed with the concept altogether:

Why do we think that human nature cannot be defined?

While natural science progressed, human science, or the Geisteswissenschaften, did not. However, the classical definition of the human being and his nature, and the formative need for cultivating virtue, was upheld as the essence of European Bildung for many centuries. In the words of Italian philosophy professor Enrico Berti, “..it remained the basis of global culture, not only Christian but also Jewish and Muslim, both ancient, mediaeval, and modern, that is of the entire culture which Aristotelian tradition has influenced; indeed, we find it irrelevant variations in Augustine, John Damascene, Richard of St. Victor, Thomas Aquinas, Leibnitz, Rosmini, Maritain and several other thinkers”.(5)

But with the advent of natural science followed a ‘spill-over’ to metaphysics: From the time of John Locke we see that his notion of the person cannot yield natural law, although he writes in the natural law tradition. For Locke, the human being cannot be known or defined because it cannot be arrived at through direct sense experience. The human being is something else than mere sensation, Locke thinks, but because he cannot sense it or observe it, it must remain unknown. This line of thought is developed further by Berkeley who argues that ‘being is preception’ (esse est percipi) and reaches it high point (or low point, as it were) in the empiricism of David Hume:

Hume does away with metaphysics altogether, but he also does away with physics: His skepticism is such that not even observations of causation count as causation: If we see a ball hitting another ball, all that we observe are two sequential occurrences - and that observation does not allow us to infer that the first ball caused the other to roll when hitting it. Hume argues that since we have seen this before, we expect the first ball to make the other roll, but this is simply a habit of ours. Since we can never observe the concept of cause, we can never know anything about it! On this ontology, there is no ontology, even less human nature that can be known – all that exists, is a series of sense experiences. Since we cannot observe ourselves, only notice our own behaviour, we have no substance or identity, all that we can know about ourselves is a series of disconnected sense experiences. In justice to Hume I should mention that he found his own philosophy entirely dissatisfactory(6), but declared that science could not help.

At this point we are faced with the delineation of the concept of science and also rationality to natural science alone. Only that which can be empirically observed and proven, can exist scientifically. While this is true for natural science; it has however never been true for the human sciences. The reductionism of science to natural science leaves metaphysics dead and philosophy ill at ease; now condemned to dealing with lesser questions than ontology and epistemology. It no longer makes sense to study the major questions of ethics when one cannot deal with the premises of ethics by meaningfully asking what human nature is like and how it can fulfill its goals.

Immanuel Kant tries to ‘rescue’ objective human nature by postulating it a priori, like an axiom of mathematics. The human being is a rational being endowed with dignity, he postulates, and therefore should not be treated as an object, a means, but as an end in itself. But praiseworthy as this may be; Kant’s postulate remains but a postulate since nothing about human nature can be known. The ethics, or moral imperative, is necessary because otherwise men would become utilitarian beasts.

Later, in the 19th century, Hegel and Fichte destroy the notion of metaphysics further, denying that essences can exist and be known: all is idea, nothing is real. And after that we find that the concept of different cultures replace human nature: the person is a ‘product’ of culture and society in both Marxism and modern anthropology. Relativism has become the very premise.

The impossibility of objective reality – sometimes dubbed essentialism – is further developed by analytical language philosophy which argues that reality cannot exist apart from language itself, it is in fact constituted by language. This school of thought is today present in the pervasive approach called constructivism in the social and human sciences: political reality, especially norms, are socially constructed. Likewise, the positivist turn in legal philosophy which underlies most European legal thought denies that there is any reality to the concept of justice: the law is what the letter of the law says.

However, given this, there is now a turn back to metaphysics in important schools of philosophy: In the Oxford and Cambridge schools of ordinary language philosophy there is a return to the classical concept of the person(7). The American philosopher W.O. Quine argues, in his famous book Word and Object (1960) that language must refer to objects that in turn give meaning to language – i.e. it is the objects that exist independently and language that describes them, not the other way round, as constructivism and analytic language philosophy would have it.

Also in the continental tradition we find very significant objections to the death of metaphysics in personalism and hermeneutics. Personalist philosophers like Jonas, Mounier, Ricoeur, and the late Pope John Paul II have emphasised that the experience of the other provides the basis for knowledge of human nature and ethics. Mounier himself states that the classical concept of person “is the best candidate to sustain legal, political, economic and social battles in defence of human rights” (Berti, op.cit., p. 10). The reason for this is entirely simple and logical: if equality is the central notion of law and politics, then this implies that there is something knowable about the human person that is the same everywhere and always. This is also the central point of my argument that human rights are a natural law concept – they demand and presuppose one common human nature in terms of the same dignity and the same equality.

Natural Law Today: Where is the Evidence?

So far we have merely shown that the Western philosophical tradition for many centuries upheld the classical notion of human nature as ‘rational and social’, and that metaphysics was side-lined by first, British empiricism which equated the human and the natural sciences, and later by increasingly skeptical strands of thought. However, much of the problem with this evolution in the history of philosophy had to do with the immense progress in empirical and natural science and the deplorable lack of such in the human sciences. But it also has to do with the confusion between the two, premised on the paradigm that human science must imitate natural science in order to progress.

However, none of this has disproved Aristotle. The argument remains that the human being can reason about ethics as he can reason about facts. The Humean criticism misses the point when it faults Aristotle with confusing ‘fact and values’, for the classical concept postulates that the person is both ‘fact and value’ in its very essence – being rational means being ethical. This point is the most foreign of all to modern man, and the very unfortunate separation of the two that Hume made has henceforth obscured the possibility of natural law.

Let us now give natural law a chance, as it were. Could Aristotle be right?

In an interesting paper the Swedish MP Per Landgren records an imaginary incidence(8):

Two persons rescue people from a burning house. They are subsequently interviewed by the paper, and the journalist asks why they risked their own life to do this. One says that he did not think about that question at all; he simply acted. But the other says that he thought that he would become rich from getting a prize for valor, that he could get famous, etc. – The journalist is puzzled over this answer. Something seems very wrong, undignified, unnatural about it.

This example illustrates the argument that natural law makes: A natural reaction is to try to save life, even if one is afraid. An unnatural reaction is to do it to make money from it. One may even say that the latter reaction is evil, bad, wrong – thus, there is a natural ability in us to discern right from wrong.

Further, saving life – one’s own and that of others – seems to be a basic value, whereas the need to make money can be many things, and varies between being a vital and good thing when one must provide for one’s family, and being a bad thing when a life-rescuer saves life in order to make money, as in the example above. Thus, ethics makes sense only in a context of telos, as Aristotle argues.

Landgren makes the point that there are some basic values that are universally recognized as such: to live rather than to die, to be respected, to be healthy, to learn, to cherish truth rather than lies, etc. op.cit., p. 120). The opposite of these values are morbid and unnatural, most people would immediately agree. These basic values are called ‘intrinsic’, Grundwerte’, ‘Rechtsguter’ (Ibid.).

The point about these values is that they are inborn, intrinsic, constitutive – they define what a human being is, just like Aristotle’s definition. This is so because we cannot derive them from any principles or logical arguments; they are simply what human beings, grosso modo, are like. True, there are mass murderers and masochists around, but we tend to describe them as aberrations, perversions, unnaturals. If we were true relativists, we would have to say that a mass murderer just has another subjective preference that ours.

Thus, when we read the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, we see that the rights therein are largely such basic principles that are commonsensical to all reasonable persons. Reasonable means, we recall, that one is upright and human; not corrupted and evil. And the author of this human nature, creator or not, does not have to be mentioned, but the rights form a whole that reflect a view of human nature that is knowable through common sense and reason. But if the concept of human nature is denied, there is no basis for these human rights – they become mere ideological and political devices. Human nature remains an axiom, as it was also to Aristotle, an essence and prime mover, as he would have called it.

But it remains fully possible to discern what human dignity and therefore human rights is about through the faculty of reason, deductive as well as inductive. The sharpness of the rational mind is a function of its ascetic and logical training, both in terms of consistent argument – ‘if all men are equal, one man cannot be discriminated’ – and ethics; “if stealing is wrong, I must refrain from it lest my ethical sense be dulled’. The problem, I think, lies not so much in lack of reason as in lack of virtue. It is rather easy to know what is right and wrong, but rather arduous and unpleasant to do what is right. As a Catholic dictum puts it, tongue-in-cheek: “A little virtue does not hurt you, but vice is nice”.

In conclusion, the relativist position is untenable and the rationalist position is possible. There is no need to discard Aristotle’s ontology, the classical notion of the person; and mere logic itself demands that the law be concerned with universals, not with subjective interests. But it remains a tall order indeed to restore rationality to Western politics.

JANNE HAALAND MATLARY is Professor of International Politics at the University of Oslo and at the Norwegian Military Staff College, Norway. She has published widely in the field of European security policy, and is currently working on the political implications of asymmetric warfare in NATO. She was deputy foreign minister of Norway, 1997-2000. She is also member of the Pontifical Council for Justice and Peace and Consultor to the Pontifical Council for the Family.

20081226

(Illustrations and image texts: katobs.se)

(1) ”Jenseits von Gut und Bøse: Vorspiel einer Philosophie der Zukunft, Wilhelm Goldmann Verlag, Munchen, 1885

(2)This encyclica is addressed to Catholics, not to all ‘people of good will’. It is thus an ‘internal’ document for the Church which addresses the role of the Church in the world. It is highly significant that the Church to non-believers can and should only be a contributor to society’s political debate on secular terms, thus sharply distinguishing between the society of believers - the Internlogik of the Church; and its external role in secular society, where it can only act and argue in natural law, secular terms.

(3) Private conversations and correspondence, 2003-2005

(4) Contra Eutychen, III, 6

(5) E. Berti, ”The Classical Notion of Person in Today’s Philosophical Debate”, paper presented at the Papal Academy of Social Science”, annual conference, September 2005

(6) See Appendix, Treatise of Human Nature

(7) I am indebted to Enrico Berti’s paper, op.cit., for the remainder of this analysis.

(8) Per Landgren, ”Naturretten – en mansklig etikk”, Chapter 5, Det gemensamma bästa – Om kristdemokratiens idegrund, Stockholm, 2002